I don't believe in creationism. I certainly understand the arguments about it, but it puts observational fact at odds of hermeneutics, and that's something that has been demonstrated as problematic, historically, for as long as Christianity has been around. To lay aside what we can apprehend with our minds strikes me as folly, not faithful.

I have two beefs with creationism that I want to outline here, realizing that many people who read this likely will be bothered that my thoughts don't parallel their own. Such is life. Anyway, here are the two points I want to stick explore: The question of literal interpretations; and the nature of the God who exists within creationism.

I have two beefs with creationism that I want to outline here, realizing that many people who read this likely will be bothered that my thoughts don't parallel their own. Such is life. Anyway, here are the two points I want to stick explore: The question of literal interpretations; and the nature of the God who exists within creationism.

Literally the Truth

It's probably no surprise that, considering the abuse it's suffered during the 21st century, I am leery about people using the word literally. Far too frequently, it's misused as a superlative instead of an adjective, which grinds this grammarian's gears. However, the issue that's deeper for me is what, precisely, in the Bible ought to be taken as literal.

Since creationism deals with the creation of the world, I'm going to pull mostly from Genesis. There are millennia of apologists to discuss what "really" is happening in the beginning of the Bible, complete with questions of translation, inference, and application, which I'm not interested in pursuing at this juncture. Instead, I want to focus on the implication of one of the basic tenets of creationism: That God literally created the world in six days.

Taken as an article of faith, I don't really have a problem with people believing that. As an article of fact, well, I'm bumping into some problems. One of them would be, which creation story in the Bible is the literal one? The one that outlines the creative process, including the creation of animals before mankind shows up? Or the one that changes the order and explains plant life coming after the creation of Adam?

Now, I'm not saying that the stories, because they don't match up perfectly, are inherently incorrect. I mean that the idea of a literal truth reading is going to be preferential and, quite often, traditional.

Of course, there are some ready-made responses to these critiques (and biblical apologists have been defending them for centuries), not the least of which is that the fine points aren't what matter: It's the overall story that matters. And I agree with that completely--which is why it's so bizarre when literal interpretations of sacred work are insisted upon. Which ones? The ones that we've received via tradition? The ones made by the oldest versions of the text? It becomes a matter of taste, which seems a slippery foundation to build upon.

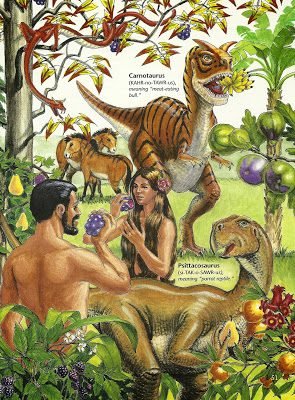

Here's the question that I can't get out of my head: When humankind finally sets foot on Mars, could a now-Martian send off a spritz of water up at the pale, distant sun and see a rainbow? That is, could rainbows exist on Mars, provided we put a human there to see it and water there to cause the effect? If the Bible's account of everything--contradictions included--is literally true, then rainbows are a uniquely terracentric phenomenon. It would also mean that there were no rainbows before Noah. The mist that is spoken of in Genesis did not, when light pierced it, refract and there was no colored spectrum visible. Of course, we're in a postlapsarian and postdeluvian world, so we can only see rainbows when light goes through suspended water molecules. Maybe there really was no such thing as a rainbow for Adam and Eve, making this little milieu anachronistic:

What it means is that the natural laws which we can observe, measure, and--to a certain extent--predict, aren't actual laws--they're more like guidelines. The exploration of our world and all of the advances that we've made by recognizing, understanding, and applying these laws were all farcical, and our progress illusory.

"Yes," some creationists may say, "that's the mystery of God. He is the only Truth and we can rely on Him to be the only true Thing."

The problem with that line is actually point number two:

Of course, there are some ready-made responses to these critiques (and biblical apologists have been defending them for centuries), not the least of which is that the fine points aren't what matter: It's the overall story that matters. And I agree with that completely--which is why it's so bizarre when literal interpretations of sacred work are insisted upon. Which ones? The ones that we've received via tradition? The ones made by the oldest versions of the text? It becomes a matter of taste, which seems a slippery foundation to build upon.

Here's the question that I can't get out of my head: When humankind finally sets foot on Mars, could a now-Martian send off a spritz of water up at the pale, distant sun and see a rainbow? That is, could rainbows exist on Mars, provided we put a human there to see it and water there to cause the effect? If the Bible's account of everything--contradictions included--is literally true, then rainbows are a uniquely terracentric phenomenon. It would also mean that there were no rainbows before Noah. The mist that is spoken of in Genesis did not, when light pierced it, refract and there was no colored spectrum visible. Of course, we're in a postlapsarian and postdeluvian world, so we can only see rainbows when light goes through suspended water molecules. Maybe there really was no such thing as a rainbow for Adam and Eve, making this little milieu anachronistic:

|

| We can be grateful for the strategically placed tiger. |

"Yes," some creationists may say, "that's the mystery of God. He is the only Truth and we can rely on Him to be the only true Thing."

The problem with that line is actually point number two:

Who's (Whose) God?

If we're willing to admit the kind of God who would disallow rainbows--which we know through our observations and our God-given intellect to be a response of natural processes--until such time as He wanted them to exist, then we're bumping into a massive theological crisis.

It's the same thing that's happening when one asks about dinosaur bones. "Did dinosaurs die in the Flood?" someone may ask. "Yes," some creationists cry. "They were created, weren't they? Only two of each (picking one version of the story and not the other) went aboard. The rest perished."

|

| Not the least accurate thing about this? They didn't italicize the names. |

So why are scientists convinced that dinosaurs--and, indeed, the Earth itself and the solar system and the entire universe--are older than what's possible in the Bible? Is this Photoshopped image of Darth Maul and some old-timey dinosaurs actually correct? Are dinosaurs a way of promulgating thoughtless, godless sheeple?

There are pretty concrete answers to why we think the world is the age that it is, how the universe began, and a slew of other things that are verified through mathematics, observations, and worthwhile hypotheses. What we bump into, however, is the fact that the bones are here. You can see them. In some cases, you can touch them. You can lick them (which is not really recommended, but it is a great way of knowing if you have a fossilized bone or just a rock...and, no, I'm not making that up). In short, they have to be accounted for.

The problem with the creationist argument, so far as I can understand it, is that it puts a strange characteristic on God: Either He allowed Satan creative powers in the form of fossil generation, or He created the fossil record in order to deceive His other creations (us).

The first one is fascinating. Not only is an argument about God allowing horrible things to happen a harsh pill to swallow, it also plays into the problem of evil in the first place, making theodicy a much harder expression, but it also raises all sorts of bizarre implications for anything that happens at all. "Why was my kid born with half a heart?" "Because Satan made his heart not work right!" I don't know when that explanation would actually be grounded in any rational approach, even for a believer. The idea that the devil is behind every nefarious thing in the world really makes mankind irrelevant. It obviates any need for free will or action, turning all of humanity into a rope that these two cosmic entities use for a spiritual tug-of-war. In a lot of ways, arguing about Satan burying dinosaur bones isn't even about fossil evidence or the natural world: It's a portion of the problem of evil question that has been discussed since at least Socrates. That isn't a conversation for this essay, so I'll leave it at that.

The second one is the argument that I hear posited more often (perhaps because it empowers God's abilities whilst diminishing Satan's). It's one that confuses me even more, though, than "Satan buries dinosaur bones" because it's essentially giving credit to an all-knowing and all-loving God who has done all sorts of sketchy things to trick us into believing His scriptures over the other set of tools He gave us with which to read the world. That isn't the sort of thing that God should do, I would think, unless this is actually who God is:

Look, if the point of creation is to make a world on which people are created as the culmination of a week-long process, then to age the stones and bones and pieces of the Earth after the fact (as one of my teachers once said, citing how Jesus turned water into wine--the best wine, which is one that has aged a great many years) in order to test the faith of those He created, then God isn't looking for worshipers--He's looking for patsies. And to be really honest, if God's down with pulling galactic scale pranks, well...okay, on one hand, that's pretty funny. That's a really long game He's playing. Tricking all of humanity into believing the Tyrannosaurus rex existed? That's a lark. But on the other hand, that's a pull-the-chair-out-from-under-a-septuagenarian kind of a prank, and that seems low.

On a serious note, it would make God appear unsure of Himself, or somehow desperate to make life more complicated than it already is. It would put life into a realm of such complete illusion that, even with God's existence, it still become without meaning. Nothing could be relied upon, save--some would argue--the love of God. But if God was tricking us about natural laws and what we can observe and deduce with our intelligence, why should we have any confidence in any of the other things that He's declared or promised?

The implications of creationism are insulting to the God I worship and those He calls His children.

|

| I don't know about it being good news if dinosaurs didn't exist. That would make me sad. |

The problem with the creationist argument, so far as I can understand it, is that it puts a strange characteristic on God: Either He allowed Satan creative powers in the form of fossil generation, or He created the fossil record in order to deceive His other creations (us).

The first one is fascinating. Not only is an argument about God allowing horrible things to happen a harsh pill to swallow, it also plays into the problem of evil in the first place, making theodicy a much harder expression, but it also raises all sorts of bizarre implications for anything that happens at all. "Why was my kid born with half a heart?" "Because Satan made his heart not work right!" I don't know when that explanation would actually be grounded in any rational approach, even for a believer. The idea that the devil is behind every nefarious thing in the world really makes mankind irrelevant. It obviates any need for free will or action, turning all of humanity into a rope that these two cosmic entities use for a spiritual tug-of-war. In a lot of ways, arguing about Satan burying dinosaur bones isn't even about fossil evidence or the natural world: It's a portion of the problem of evil question that has been discussed since at least Socrates. That isn't a conversation for this essay, so I'll leave it at that.

The second one is the argument that I hear posited more often (perhaps because it empowers God's abilities whilst diminishing Satan's). It's one that confuses me even more, though, than "Satan buries dinosaur bones" because it's essentially giving credit to an all-knowing and all-loving God who has done all sorts of sketchy things to trick us into believing His scriptures over the other set of tools He gave us with which to read the world. That isn't the sort of thing that God should do, I would think, unless this is actually who God is:

|

| Not Tom Hiddleston. More people would be believers if God were Tom Hiddleston. I mean Loki. |

On a serious note, it would make God appear unsure of Himself, or somehow desperate to make life more complicated than it already is. It would put life into a realm of such complete illusion that, even with God's existence, it still become without meaning. Nothing could be relied upon, save--some would argue--the love of God. But if God was tricking us about natural laws and what we can observe and deduce with our intelligence, why should we have any confidence in any of the other things that He's declared or promised?

Dude, Are You an Atheist?

No. But there's a greater subtlety to God's machinations than I think people go for at first blush. I think the problem of evil is a severe one, and no amount of "it's agency, man!" sits well for me. (If Paradise Lost doesn't fully convince me of that part of the argument, no argument on the internet is going to help out.) There are immense gaps that I'm fine with letting faith fill, but I think it's an insult to the brains we were given to dismiss what we do and can know. It's like Hamlet's speech in 4.4:

Sure, he that made us with such large discourse,Fust means to go moldy or to decay. It doesn't make sense to Hamlet--and it doesn't make sense to me--that God would give us the ability to discern reason (and "Truth is reason") only to let it wallow and rot in us, to lie fallow when there's so much that we can learn. Ignorance is no pathway to salvation. I'm part of a religion that thinks that if it's true, it's part of my religion--not the other way around. Truth has been around longer than Mormonism--and longer than the dinosaurs, too.

Looking before and after, gave us not

That capability and god-like reason

To fust in us unused.

The implications of creationism are insulting to the God I worship and those He calls His children.

Comments