What do we hope to gain out of the fiction that we read?

My friend today shared some of her students' feelings about Pride and Prejudice. What surprised her was that, despite how much they enjoyed learning about the Regency era and all of the fine points from a book of manners, few of them wanted to read another Jane Austen book, preferring their "fantasy, action books" instead. As a writer and consumer of many of those "fantasy, action books", I decided not to take umbrage at the implied inferiority of my adoptive genre. But it raises the question with which I started this essay: What is our purpose in reading?

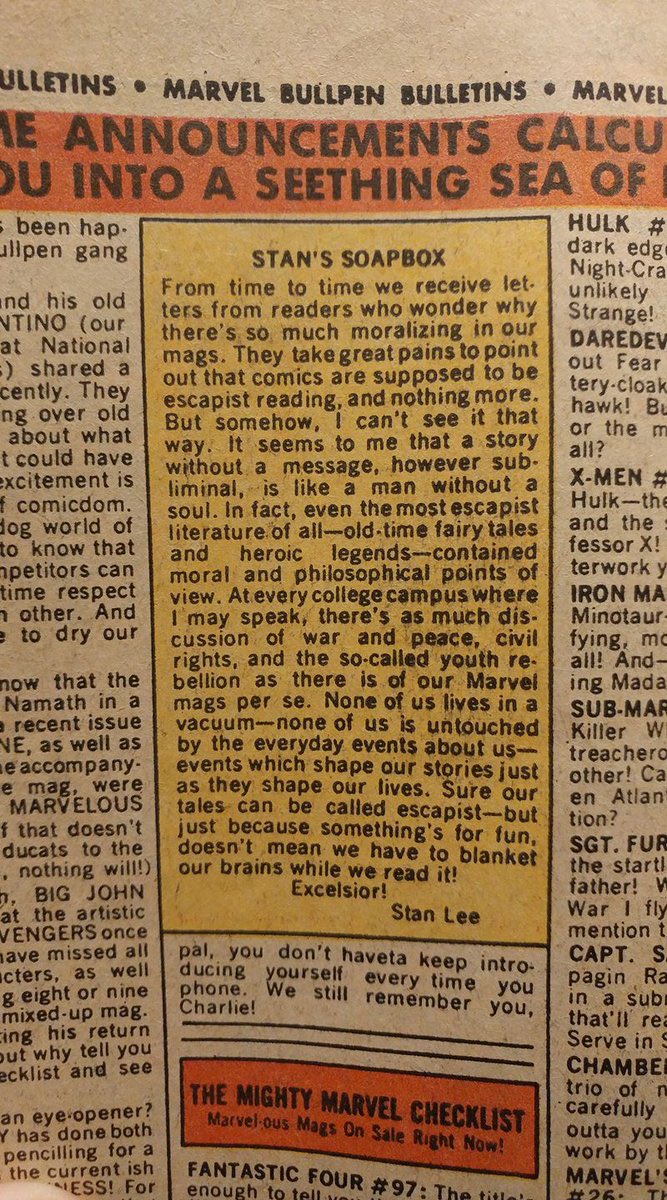

Stan Lee, creator of Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four and basically the largest corrupter of American understanding of what radiation actually does to human beings, had this interesting insight that he once shared in his Bullpen--a random collection of fan mail, thoughts, and comments from Marvel writers and readers:

While the literary and philosophical merits of comics are beyond what I'm exploring here (perhaps another time), Lee's comments here emphasize my point: There's an assumption about what reading [fill in the blank] is "supposed" to do, built upon genre conventions, economic pressures, and traditions within publishing. Sometimes people whine when comics "take themselves too seriously" and aren't "escapist" enough--others whine when comics are too frivolous and don't take themselves seriously enough. Aside from the realization that you can't please everybody, I feel that this is a way of becoming fictionally ossified.

When I ask what we hope to gain from reading, I'm not satisfied with axiomatic responses: "To learn about good and evil!" "To learn about Truth!" "To understand other points of view!" None of these is wrong, necessarily, but neither do I see the answer. Look, good and evil, transcendental truths, and other points of view exist outside of fiction. We don't have to go to made up stories when those real experiences could be just as instructive. I don't have to rely on Maniac Magee to teach me about the ills of racism; I could read Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s writings instead. I don't have to rely on The Lord of the Rings to learn that those of least apparent consequence can often be what best stands up to totalitarianism and dictatorships; I could study the life of Gandhi. So these lessons are in the makeup of our history, the memetic inheritance we are born into. We don't have to have these transcendental aspects of our humanity dramatized and fictionalized...do we?

Maybe that's why we love stories, though. It's softer than history's rough edges. We can't shut the book on the Trail of Tears and say, "That makes me uncomfortable. I'm not going to finish reading it." The terror of Jackson's administration was real--still is real. But if it's a story? If it's simply Dances With Wolves that's on TV? We can turn it off, shut the book. The pain of American exceptionalism needn't be unfolded on real, living people. It can be a story. It can be "fake" and its hurtful pieces pushed aside.

But we've all read something that makes us recognize something better about life and the human condition, something that we better understood because of fiction. The Harry Potter series has done this for millions of people, so much so that studies have shown a correlation between those who've internalized the messages of the series and increases of empathy. My life has been inexpressibly enriched by my reading of Shakespeare*; a coworker, the writings of Homer; a student, the thoughts of Cicero; another, the book Things Fall Apart.

Our fiction obviously does something to us that reality doesn't do--or perhaps, we aren't willing to let happen to us. I'm not sure. Nevertheless, there's something that fiction can do, maybe even better than reality. I won't argue that there's no difference between qualities of fiction, of course. I think that's fairly obvious. I do wonder, however, what we are aiming to get when we pick up some book or other--and what that says about us.

---

* The title of this essay comes from Hamlet.

My friend today shared some of her students' feelings about Pride and Prejudice. What surprised her was that, despite how much they enjoyed learning about the Regency era and all of the fine points from a book of manners, few of them wanted to read another Jane Austen book, preferring their "fantasy, action books" instead. As a writer and consumer of many of those "fantasy, action books", I decided not to take umbrage at the implied inferiority of my adoptive genre. But it raises the question with which I started this essay: What is our purpose in reading?

Stan Lee, creator of Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four and basically the largest corrupter of American understanding of what radiation actually does to human beings, had this interesting insight that he once shared in his Bullpen--a random collection of fan mail, thoughts, and comments from Marvel writers and readers:

|

| I love that sign off. Excelsior! |

When I ask what we hope to gain from reading, I'm not satisfied with axiomatic responses: "To learn about good and evil!" "To learn about Truth!" "To understand other points of view!" None of these is wrong, necessarily, but neither do I see the answer. Look, good and evil, transcendental truths, and other points of view exist outside of fiction. We don't have to go to made up stories when those real experiences could be just as instructive. I don't have to rely on Maniac Magee to teach me about the ills of racism; I could read Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s writings instead. I don't have to rely on The Lord of the Rings to learn that those of least apparent consequence can often be what best stands up to totalitarianism and dictatorships; I could study the life of Gandhi. So these lessons are in the makeup of our history, the memetic inheritance we are born into. We don't have to have these transcendental aspects of our humanity dramatized and fictionalized...do we?

Maybe that's why we love stories, though. It's softer than history's rough edges. We can't shut the book on the Trail of Tears and say, "That makes me uncomfortable. I'm not going to finish reading it." The terror of Jackson's administration was real--still is real. But if it's a story? If it's simply Dances With Wolves that's on TV? We can turn it off, shut the book. The pain of American exceptionalism needn't be unfolded on real, living people. It can be a story. It can be "fake" and its hurtful pieces pushed aside.

But we've all read something that makes us recognize something better about life and the human condition, something that we better understood because of fiction. The Harry Potter series has done this for millions of people, so much so that studies have shown a correlation between those who've internalized the messages of the series and increases of empathy. My life has been inexpressibly enriched by my reading of Shakespeare*; a coworker, the writings of Homer; a student, the thoughts of Cicero; another, the book Things Fall Apart.

Our fiction obviously does something to us that reality doesn't do--or perhaps, we aren't willing to let happen to us. I'm not sure. Nevertheless, there's something that fiction can do, maybe even better than reality. I won't argue that there's no difference between qualities of fiction, of course. I think that's fairly obvious. I do wonder, however, what we are aiming to get when we pick up some book or other--and what that says about us.

---

* The title of this essay comes from Hamlet.